The moonlight filtering through the garden’s ancient, gnarled olive trees casts dancing shadows on the ground. A young man, muscled and toned from years of outdoor living, frequent walking and laboring as a carpenter kneels alone on the cool soil, a few yards from three friends who have fallen asleep.

Just minutes before, the young man’s festive mood had changed from one of peace and strength to sorrow and deep distress. He expresses as much to his friends and asks them to sit and watch with him while he goes to pray. But they can’t. They’re tired after the long day, and their full stomachs following the special celebration meal have made them sleepy.

The young man’s distress is verbalized in his prayer. “Please, Lord, take this cup from me.” Clearly he would rather not do what he’s being asked to do. He prays, and then, agitated, rises to check on his friends, or be encouraged by their presence.

But they are sleeping, and the young man chastises one of them for not being able to stay awake with him, to support him and keep watch. Danger is lurking. The young man knows it’s only a matter of time before it arrives, and he doesn’t want his dearest friends to be blindsided by it. They don’t have a clue what’s about to happen. “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak,” he tells them.

He again admonishes them to watch and pray, and then returns to his spot to continue his beseeching conversation with God. Then he checks on his friends again, who have once again fallen asleep. Again he admonishes them and warns them to stay awake before he returns one more time to his prayer.

This time his distress becomes severe, and he sweats so profusely that his pores ooze drops of blood. It looks as though the life is draining out of him, weakening him physically. But he makes his decision, accepts his fate, and rises to meet his friends for the final time before being grabbed and arrested in front of them and dragged away for trial.

A closer look—

Most of you are probably familiar with this story—Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane with his disciples after their Passover meal. Jesus selecting three of his closest disciples to follow him farther into the garden to sit, watch, and pray while He beseeches His Father to remove the punishment and suffering of the cross that he’ll soon have to endure.

In this story, Jesus displays both his physical and spiritual sides. Acutely. But can you tell what he is more of—physical or spiritual?

Body, Mind, Spirit? Or all three—

He craves the physical closeness and emotional support of his friends. He seems to crave assurance that they have his back. When he discovers—two times—that they don’t, he is angry and calls them out for their weakness. Their physical weakness, not their spiritual deficiency. He recognizes them for what they are—weak men who have difficulty overcoming their body’s physical needs and desires. And he warns them about the dangers of letting the physical overrule and control the spiritual.

By the third time, he confronts them again, but essentially tells them it doesn’t matter anymore. The peace of the night (for them) is over. Indeed, life as they have been living it will abruptly cease within hours.

Being God incarnate, Jesus was spirit, The Word itself. But He was also physical, that spirit encased in flesh. On this night, he demonstrates both the body and the spirit to the extremes.

What about us?

Is it realistic to expect us to do any less? Especially since we are not God in the flesh—we are not God at all—and we are more likely to battle with our body’s frailties, shortcomings and demands than Jesus.

On that night He demonstrated both body and spirit. Yes, the Spirit won the battle over the body for Him, but that does not detract from the fact that His body suffered immeasurably, and would suffer even more when it is beaten, pierced and hung soon after His arrest.

Our Lord suffered physically, emotionally and spiritually, a triad of pain.

Body, mind and spirit.

If our Lord suffered so, how can we expect to be spared from sometimes being more body than spirit, not an equal balance of both, or times when we manage to be more spirit than body?

And you?

What has your experience been?

Until next week,

Rejoice in the complexity of being both body and spirit!

Andrea

May you prosper in all things and be in health, just as your soul prospers (3 John 2).

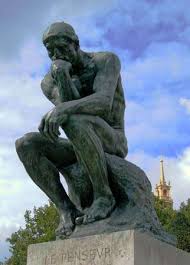

Photo by Antoine Perier

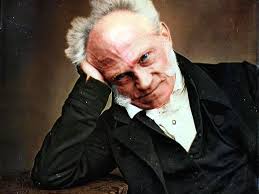

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) A German philosopher, like Hegel, Schopenhauer is considered to be a true pessimist. He believed life is evil to the core, and pain and suffering are unavoidable. He is the father of Existentialism, although the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines Existentialism as chiefly a 20th Century philosophy.

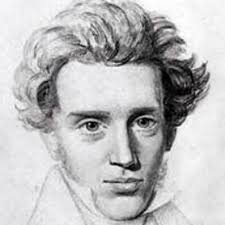

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) A German philosopher, like Hegel, Schopenhauer is considered to be a true pessimist. He believed life is evil to the core, and pain and suffering are unavoidable. He is the father of Existentialism, although the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines Existentialism as chiefly a 20th Century philosophy. Soren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855) Kierkegaard, a Dane and deeply religious thinker, believed that God’s existence cannot be proven. But he believed that a religious leap of faith could make our lives bearable and meaningful. He is regarded as a Theist—someone who believes in a God as the creative source of the human race and the world who transcends the world but is immanent (being within the limits of possible experience or knowledge) in it. Most theists regard God as a creator who stands back from His creation without getting too involved it.

Soren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855) Kierkegaard, a Dane and deeply religious thinker, believed that God’s existence cannot be proven. But he believed that a religious leap of faith could make our lives bearable and meaningful. He is regarded as a Theist—someone who believes in a God as the creative source of the human race and the world who transcends the world but is immanent (being within the limits of possible experience or knowledge) in it. Most theists regard God as a creator who stands back from His creation without getting too involved it.

John Dewey (1859 – 1952) An American! Dewey was considered to be a pragmatist—someone guided by practicality and that “the function of thought is to guide action.” He considered democracy to be a way of life, and that democracy should be promoted and pursued by a rational and effective educational system. Dewey has had a profound impact on both the American educational and political systems.

John Dewey (1859 – 1952) An American! Dewey was considered to be a pragmatist—someone guided by practicality and that “the function of thought is to guide action.” He considered democracy to be a way of life, and that democracy should be promoted and pursued by a rational and effective educational system. Dewey has had a profound impact on both the American educational and political systems. Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) Camus was an atheist who was an existentialist. He believed humans must establish their own dignity, despite a meaningless life.

Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) Camus was an atheist who was an existentialist. He believed humans must establish their own dignity, despite a meaningless life. C.S. Lewis (1898 – 1963) A former atheist, the British and Oxford don, Lewis, became the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th Century. He is the esteemed author of the famous Chronicles of Narnia series, as well as Mere Christianity, and was a close friend of the Lord of the Rings trilogy author, J.R.R. Tolkien. Both men were members of the Inklings, an informal literary discussion group associated with Oxford, England.

C.S. Lewis (1898 – 1963) A former atheist, the British and Oxford don, Lewis, became the greatest Christian apologist of the 20th Century. He is the esteemed author of the famous Chronicles of Narnia series, as well as Mere Christianity, and was a close friend of the Lord of the Rings trilogy author, J.R.R. Tolkien. Both men were members of the Inklings, an informal literary discussion group associated with Oxford, England.