It’s all about thanksgiving.

I’m going to guess all of you reading this post have experienced a major life event you considered to be more of a thorn in your side than a blessing you’d give thanks for. No doubt 2020 has rocked your world with COVID-19 and maybe brought accompanied economic devastation.

It hasn’t been a normal year for anyone, or an easy year for many. We’ve all been turned on our heads to some degree.

It’s been a thorn.

We don’t like thorns. They’re sharp and often draw blood. They might leave bruises or infections that take time to heal. They certainly make life harder to handle.

But there are profound life-growing lessons to be learned from painful, blood-drawing thorns, and joy can result from them. For it’s in life’s thorns that we learn more about ourselves, become humbled, and learn how to persevere.

They can also—if you’re willing—turn us toward God and make us more reliant on Him.

But even with these thorns, we have so much to be thankful for. So I’m going to focus this post on our upcoming American holiday, Thanksgiving. It’s a special day to focus solely on giving thanks; a day set aside to express gratefulness with and for family and friends, even if you have to celebrate and thank them via ZOOM.

While we don’t often think about celebrating or giving thanks for the thorns in our lives, they may be the first and most important things we should look to and have at the top of our “I’m thankful for…” list.

Even the Pilgrims, who are officially credited with celebrating the first Thanksgiving nearly 400 years ago, (we were supposed to have a big 400th anniversary celebration for their arrival this year), had encountered thorns prior to that celebration. Deadly ones. And the fact that any of them were still alive to tell about it may be the reason they gave thanks.

Pilgrim basics: my heritage—

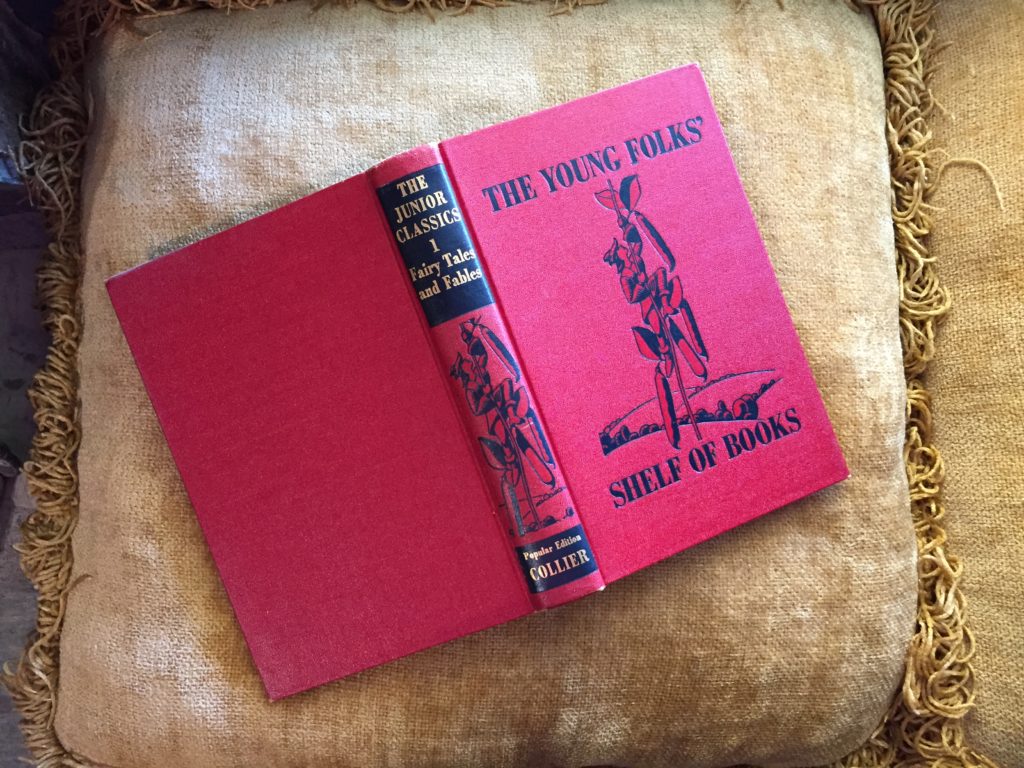

Thanksgiving is special to me. It should be, since I’m a direct descendant of two Pilgrims who sailed from England to America in 1620. Actually, one was an true Pilgrim (Separatist) and the other was a cooper (barrel maker) who evidently wanted a change of scenery and a new life in a new land.

The group was a little band of mostly like-minded pioneers who wanted to worship God without fear, persecution or worldly influence in a way of their choosing. They bravely sneaked away to England on a tiny ship after signing a contract with an English company to plunk down a colony on our shores and start successful trading and businesses.

(On a side note, don’t confuse Pilgrims—Separatists, who wanted to completely separate from the Church of England—and the Puritans, who wanted to transform and purify the Church from the inside.)

When I think about the accounts of that first Thanksgiving—the three-day feast the Pilgrims celebrated with the Wampanoag Indians—I wonder just how many of them were thinking: “I’m so thankful.”

As the History Channel’s website, history.org, states:

“As was the custom in England, the Pilgrims celebrated their harvest with a festival. The 50 remaining colonists and roughly 90 Wampanoag tribesmen attended the “First Thanksgiving.”

One of the attending Pilgrims noted a Pilgrim attendance of 53, but let’s not quibble in numbers.

It was customary for these English people to celebrate a bounty with a feast and recreational activities, so that’s what they did. Food and sport. And they invited the Indians. (Yes, they really did.)

They were grateful to the Indians, especially for one of them who intervened early and miraculously in their lives to teach them how to add fish to the soil to improve the growing conditions for a good harvest.

They hadn’t expected the poor soil conditions in Massachusetts. It was not where thy planned to land and live. Farther down the coast in Virginia was the landing plan, but they had arrived too late in the season and had to settle for the more northern location.

They also missed planting adequately for the growing season in cold, bitter Massachusetts with its poor crop-growing soil. Their food rotted and became infested with bugs. Then disease, starvation and freezing temperatures decimated most of their tiny band of 102 immigrants in the first six months.

And this is where it gets personal.

My great, great, great, great… Pilgrim grandmother, Priscilla Mullins, arrived at Plymouth in Massachusetts with her brother and their two parents, ready and likely excited to start a new life. But within months, the teenager’s mother, father, and 14-year old brother had succumbed to disease and starvation, leaving her alone with the other survivors, which included only three other women. Her family, along with the other dead, was buried in unmarked graves.

Priscilla was suddenly an orphan in a strange, scary land.

A year later, what could she have been thankful for?

Was she at all thankful for those torturous thorns in her life?

I can only speculate, but knowing that she was a devout follower of Jesus Christ, I’m going to guess that she had a few items on her thankful list.

My thorns—

About twenty years ago I started deliberately thanking God for the thorns He’s allowed me to get skewered by in my life. Why? Because it’s been in and through these thorns that I’ve grown the most emotionally and spiritually.

My thorns remind me that I’m really a helpless, puny human without much control over my life, although I often entertain, placate and blind myself by thinking I have more control over it than I do. The thorns keep my humble, relying on Someone greater than myself. The One who’s always in control. And that keeps me focused on and centered in my faith.

Surely, the memory and aftermath of being punctured by my thorns still hurts. After all, thorns do make you bleed. And they can leave nasty scars. Yet they have a tendency to remind you where you’ve ben, what you’ve survived, Who really got you through them, and where you should be going.

A (shocking?) admission—

What I’m going to write may shock or offend some of you, while others will nod their heads in collective sympathy and understanding.

As much as I still grieve and lament over my infant daughter, Victoria’s, death; as much as I still long to have her here with us; as much as I day-dream at every stage of life what she would look like and be doing, and mentally replay the dreams I had for her, I am grateful—thankful—that I walked that dark, horrible, thorn-ridden road. Because doing so brought me into a vivid, eternal life with the Supreme giver of life. A deeper, more fruitful, fulfilling and joyful life in the here and now, and in the eternal.

I’d like to think that it really didn’t need to happen that way. But in my heart, I know it did. I would have kept going just as I was, with one foot in the world and the other on a spiritual banana peel.

I’m thankful for those thorns. They remind me to Whom I belong, to Whom Victoria belongs. And they remind me that I will one day see my daughter face-to-face. And I will rejoice that we’ll spend eternity together. They give me one more reason to look forward to heaven.

Each year I move closer to that precious reunion celebration.

And give thanks.

Back to my Pilgrim family—

So what was Priscilla Mullins thankful for that cold fall day?

I can only guess.

Even though she was a firm believer in God, His word, and His promises, I suspect she went through the normal stages of grief all of us encounter: shock, fear, denial, anger, depression, exhaustion. Being a Christian doesn’t make you immune to suffering the effects of losing a loved one, of experiencing profound loss.

Being a Christian does mean, however, that you experience something in addition.

It means you grieve with hope, rather than without it.

Your grief is hopeful, not hopeless.

Priscilla may have sat at the table, thanking God for His protection over her and the other survivors, for the memory of her parents and brother, for the hope of the future, and probably for the new man in her life—John Alden, with whom she would have 10 children and produce more descendants in the United States than any other Pilgrims.

I often think of her and wonder if her unwavering faith and prayers for her children and children’s children paved the way for the blessings I’ve received in my life. Many of my blessings may be the result of her generational faithfulness.

For that, I also give thanks.

As my older son once said to me while he was in college, after making some big mistakes and suffering for them, and struggling against events not in his control: “I wouldn’t change a thing about my life. I don’t regret any of the mistakes or the problems. Because they all make me the person I am today.

And that person he is today just became a first-time father last Thursday morning to a beautiful, precious baby girl. Another descendant who made me a grandma.

I have been praying for this baby—Baby Ellie—for months. My heritage, my reward.

I’m counting a plentitude of blessings this year.

And I’m sure you can count both thorns and beauty in your life this Thanksgiving!

Invitation—

- What the thorns you’ve experienced in life?

- Did you consider these thorns blessings in any way?

- How is it possible for you to be thankful for them?

- How did God see you through them so they might become a blessing?

Next week, we’ll look at Advent and the importance of celebrating the coming of Christ more than two thousand years ago, and His future coming.

Until then, may joy and thanks abound this Thanksgiving Day. I’m going to guess you’ll never forget your 2020 Day of Thanks!

Blessings,

Andrea

“Beloved, I pray that you prosper in all things and be in health, just as your soul prospers” (3 John).

Andrea Arthur Owan, M.S., A.T., R., is a fitness pro, speaker, award-winning inspirational writer, memoirist, and senior-ordained chaplain (IFOC). She helps people thrive physically, emotionally, and spiritually, and recover from grief, loss and trauma.