THERE IS OFTEN A SPECIFIC DIFFICULTY to combat in grieving, and that difficulty is our attitude.

Changing our attitudes about grief and the grieving process is hard. Even if you want to change your attitude, behavior and grief language (see last week’s post), your family members and friends may resist.

It’s important to examine our beliefs about grief—what good grieving looks like, how you talk about it and address it. I’ve had to examine and reshape my grief attitudes.

Change is often difficult.

But it can be critical to your grief recovery.

Having a safe space to grieve and express yourself—

You need to feel safe and may find grieving and grief recovery/completion is best done in a group of like-minded, understanding people. People who are also walking a similar path you’re on, or those who can walk beside you to help you in the process.

Old, stifling ideas about grief may be holding you back. It may take someone with experience and training, looking in from the outside to help you recognize where change should and can occur.

As the experts at the Grief Recovery Institute remind us:

“It is very easy to do things just the way we have always done them. But traditions generally signify familiarity, not always value.

“…even very willing people sometimes cling to old, ineffective ideas. It may be a struggle for you to let different and better information in.”

Evaluating what you’ve been taught about grief—

From a young age we’re usually given wrong, often detrimental signals and instructions about how to deal with grief and sadness. These lessons or signals can affect us the rest of our lives and make future, successful grieving difficult or impossible.

Some of us grew up in environments where our families tolerated few if any human feelings or outward expression of emotions. And now that we’re adults, our siblings and family members may still balk at or reject our need to self-express.

Those experiences can permanently color your world, and often not with a pleasing palette.

You need to paint your own grief picture—with your own emotions.

Tell your own story.

You’re the protagonist in it, and you—not others—need to provide the ending.

Make grief personal—

To complete your grieving, you’ll want to communicate your wants, your needs, your thoughts and your feelings. Not what you think someone else wants you to feel, or what someone else has told you to feel, but honestly communicate what’s going on in your mind and heart.

It’s not about feeling dumb or smart. It’s about tuning into your sadness, your joy, your deepest emotions and being able to express them. Working through the intricacies of the loss. Weaving a unique and complete tapestry.

Learning to identify and communicate your individual, positive or negative feeling and then moving on to uncovering, identifying and dealing with the next one.

You can’t move on to the next feeling if you haven’t dealt sufficiently with the one that came before it.

The danger of ignoring and suppressing emotions—

We often think ignoring an emotion will make it disappear and stop bothering us.

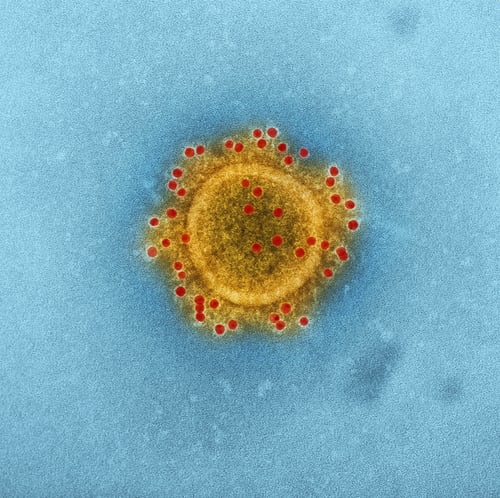

Unfortunately, that’s not what usually happens. The brain remembers, and the body keeps the score.

Suppressing your emotions can lead to a build up that eventually gets unloaded like a pressure cooker erupting and scalding everyone around it.

And when you don’t allow others to express their emotions, you’re likely to be the one getting scalded.

Another danger of suppressing sad emotions is all the energy it takes to do it. It’s hard on the physical body to keep them suppressed. And all that suppression often ends up putting pressure on your physical body. The stress causes chronic inflammation that can lead to devastating illness—both mental and physical.

Don’t be afraid of emoting with tears—

Ever heard a parent say this to a child? “I can’t understand you when you’re crying. Stop crying so I can hear you.” (I’m cringing because I’m sure I’ve said it to my kids at least once.)

While it may be true that the parent is unable to understand a child’s speech through the crying, a child probably interprets a different way—that it’s not okay to cry when expressing emotion.

So, the first thing you remember as a grieving adult is: I shouldn’t cry while sharing my emotions with someone. It’s a sign of weakness, and they probably won’t like it.

But in order to successfully and comfortably express your grief emotions, it’s important that you not feel judged; and that you do not give the impression of judging others when they’re expressing their personal emotions.

One last thought—

Before we leave today’s session, I want to leave you with one last thought from the Grief Recovery Institute, which expresses all we’ve addressed in this and previous posts:

“Unresolved grief is cumulative and cumulatively negative. Unresolved grief does not go away by the counterproductive nonactions of trying not to fee bad or by replacing the loss or by grieving alone or by being strong or by keeping busy or by the passage of time.”

All the things we’ve likely learned along life’s way need to be changed.

The question is: Are you ready to complete your grief healing?

Invitation—

I invite you to answer and work through the following questions:

- What kind of family dynamics, training or signals affected your emotions? The way they/you handled loss?

- Can you identify any loss you haven’t fully grieved, or any uncompleted/unresolved grief?

- In regard to that grief, what emotions did you have that you didn’t express or didn’t feel you were allowed to express?

- If you wanted to cry and didn’t, why not? Who or what stopped you? Would you feel comfortable crying now, even if the loss happened years ago?

NEXT WEEK we’ll explore the many short-term behaviors we resort to in grief that temporarily relieve our grieving emotions and energy. You won’t want to miss it!

Until then, open yourself to a new attitude toward loss and grieving. Give yourself and others the space needed to resolve grief.

Blessings,

Andrea

Andrea Arthur Owan, M.S., A.T., R., is a fitness pro, award-winning inspirational writer and senior-ordained chaplain. She works and writes to help people recover from trauma, grief and loss and to thrive — physically, emotionally, and spiritually.